The Role of the Church and Other Public Health Providers in the Fight against HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa

WCIU Journal: Health and Disease Topic and Area Studies Topic

February 7, 2020

by Kalemba Mwambazambi

Kalemba Mwambazambi is Professor at Université de Kananga (UNIKAN) and Registrar (Secrétaire Général Académique) at Université Protestante au Coeur du Congo (UPCC) in Democratic Republic of Congo. He holds a PhD in Missiology from University of South Africa and Doctor of Health Sciences at Keiser University in Florida (US). He does research across the globe on transformational leadership, HIV and AIDS, Christian mission, African theologies, socio-political issues, peace, justice, and reconciliation.

Understanding the HIV/AIDS Pandemic and Its Impact in Africa

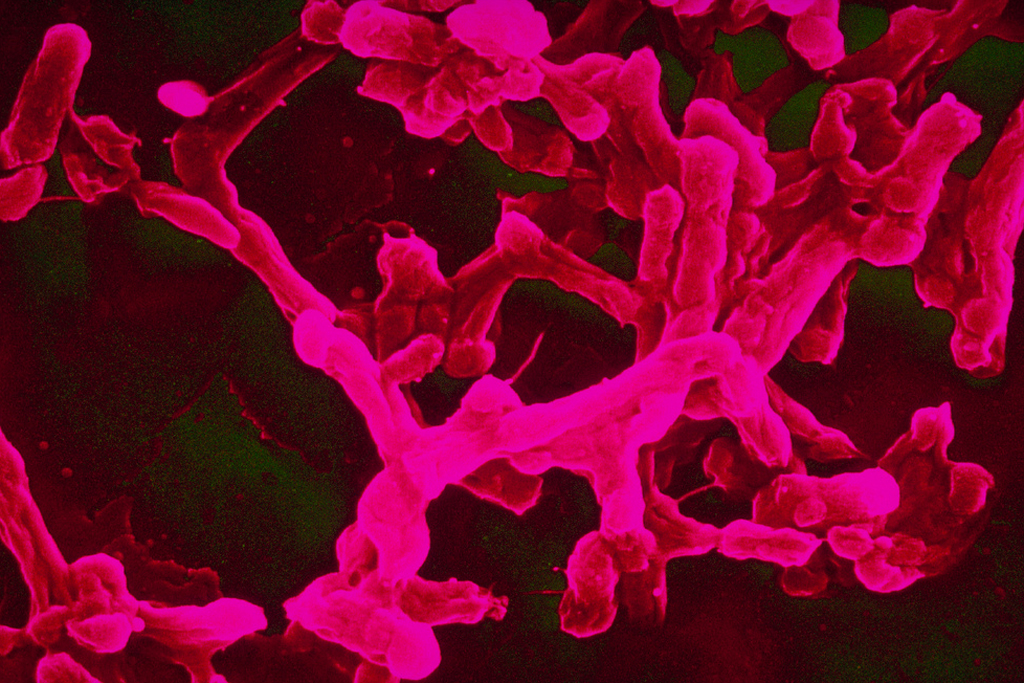

The Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) have been a ruthless and terrible challenge to the world and particularly to the African continent, which is already in a multifaceted and multidimensional crisis (cultural, socio-political, and economic). The HIV/AIDS pandemic is a drop of water in a bucket already overflowing. It relates to many other social scourges such as poverty, corruption, violence against women, xenophobia, child abuse, racism, ethnic conflicts, wars and political-military issues, paedophilia, international injustice, and discrimination based on sexual orientation. Due to HIV/AIDS, the poor get poorer, children become orphans, widows become dispossessed, and they are sometimes thrown out of their own families.

UNAIDS submits that Sub-Saharan Africa bears a disproportionate share of the global HIV burden. In mid-2010, about 68% of all people living with HIV resided in sub-Saharan Africa, a region with only 12% of the global population. The 1.9 million people who became newly infected with HIV in 2010 in sub-Saharan Africa represented 70% of all the people who acquired HIV infection globally (UNAIDS 2011, 24). South Africa’s HIV epidemic remains the largest in the world, with an estimated 5.6 million people living with HIV in 2009 (UNAIDS 2011, 24). According to Pongo, more or less 100 people, aged 15 to 45 years, are infected daily with HIV/AIDS in Africa, and the majorities are in sub-Sahara Africa, with over 70% of those infected being women (Pongo 2018, 49).

The scourge of the virus and the disease has brought about much bewilderment and tears to individuals, families, and communities. The disease progresses at an exponential rate and can destroy entire African families. It has been slowly but surely decimating millions of youth and adults who have contracted HIV by voluntary or involuntary sexual intercourse or by contact with sharp objects contaminated by HIV positive blood.

Due to the pandemic, children and the elderly often have to play new and strange roles of caring for the children of the deceased family members. In sub-Saharan Africa, 11 million small Africans under 15 years are orphans because their parents died of AIDS, one after the other. “By 2010, 20 million children had lost at least one parent to the disease” (Lekalakala-Mokgele 2011, 2). UNAIDS & UNICEF (2004) estimates that “in sub-Saharan Africa, millions of children are growing up without parents and often live with grandparents.” Schatz and Ogunmefun state that “many persons affected by HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa remain at home, with the main burden of their care resting almost entirely on family members, who in most cases are elderly females (Schatz and Ogunmefun 2007, 1392). Makiwane et al (2004, 9) affirm: “HIV and AIDS attack mostly the reproductive and economically active section of the population, changing family composition by decimating the young adult population and creating elderly female-headed and children-headed families.”

Often these senior caregivers do not receive the help they need from members of the extended family due to economic difficulties. Thus, Lekalakala-Mokgele (2011, 1) argues, the “AIDS pandemic has direct and indirect effects which have manifested in a set of interrelated social, economic, and psychological dimensions that could ultimately impact the health and well-being of the elderly.”

Although progress has been made in treatment and prevention, new cases of HIV and AIDS-related death are still many. To understand why this disease continues to spread in sub-Sahara Africa, and how it can be contained, it is important that we understand African concepts of family, sexuality and how Africans view the origins of HIV/AIDS.

African Perspectives that Relate to the HIV/AIDS Crisis

African Concept of Family

When an African is infected by the HIV virus, it affects the whole family. The African extended family has traditionally nourished its sick and absorbed its orphans without legal process. This is because African families emphasize the existence of the other, as underlined by the saying, “I am because you are” (Kalemba 2017, 38). Thus, the reaction of the African family (whether restricted or extended), when a member is affected by HIV, is in solidarity with the patient.

The nature of the African family is centered on the father, mother, children, grandchildren, and paternal and maternal uncles along with their children. In the traditional conception, the African family is integrated into clusters of relationships linking it to other community members. Society depends on alliances, customs, traditions, and solidarity which, in turn, spontaneously feed back into the extended family. Despite many changes due to modern education and cultural intermingling, the family remains an important part of African society.

African Concept of Sexuality

For both traditional and modern Africans, families are unlikely to link the spread of HIV/AIDS to sexual acts. Because sex is a taboo subject, parents as well as church leaders face a huge challenge when they have to talk about sexuality with their children and/or church members. Many feel ashamed about sexual teachings. The downside of this is harmful to young boys and girls who discover the reality of sex by curiosity, media influence, or friends, unprepared by their families or church. Consequently, young sub-Saharan Africans are often exposed to direct or indirect HIV/AIDS contamination due to ignorance, prostitution, adultery, sex outside marriage, etc. (Ramos et al 2000).

African Understandings of HIV/AIDS

Rather than acknowledge the means by which the disease is spread, most of sub-Sahara Africa’s least educated consider HIV/AIDS as a disease spread by evil spirits and witchcraft to harm African development and destroy family members (Adogame 2007, 479). Explaining the contribution to this belief by African Pentecostals concerning HIV/AIDS, for example, Adogame shows the important roles evil spirits play in diseases and ill-heath of people reporting: “The paraphernalia of the devil has expanded to include everything that poses a roadblock to the attainment of good health and wealth. There are frequent references to the spirit or demon of disease, illness, HIV/AIDS, barrenness, death, doubt, adultery, poverty, lying, drunkenness, etc.” (Adogame 2007, 479). This author observes that later healing and deliverance from demons are perceived as power encounters. Thus, any approach to Christianity and to spiritual warfare that neglects or ignores the three-dimensional balance of allegiance, truth, and power encounters is considered incomplete.

Some African Christians consider HIV/AIDS as God’s punishment for immoral people (Dill and de la Porte 2006, 23). Fortunately, many other African Christians have started to understand the problem of HIV/AIDS and its causes so that they are able to handle the problem more comprehensively, including spiritual, social, medical/pathological, and psychological aspects. Adogame declares that understanding disease and healing “must be located within the wider realms of personhood, society, life, and thought. Healing is defined in holistic terms: taking on the physical, psychological, spiritual, mental, emotional, and material dimensions” (Adogame 2007, 479). Thef conception of HIV/AIDS as a sinners’ disease is debunked both in words and deeds. Church goers are also found among people who live with HIV; many of them have equally died of AIDS. Adogame continues, “HIV/AIDS is no respecter of persons, age, class, gender and social status; this approach debunks the myth in which AIDS is perceived as a sinners’ disease, a notion that has generated controversy within many Christian churches” (Adogame 2007, 481). While this disease can be attributed in part to sinful behavior, other factors are also responsible for spreading it to innocent people, such as poverty, irresponsible actions, and a lack of appropriate means of prevention. Each of these causes can be addressed by a combination of focused efforts by family, public health providers, the government, and the church.

Stemming the Spread of HIV/AIDS

Containing the spread of HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa requires a strong public health providers’ responses and poses an enormous challenge for them in countries that are already weakened by such other evils such as poverty, wars, corruption, social injustice, and political conflicts. HIV/AIDS affects everyone and everything. For this reason it is necessary to rethink the government and community task towards HIV/AIDS and piety, which demonstrates that all life is sacred and God is in control of everything. It is time to work hand in hand to fight this scourge, avoid dogmatic indifference, and promote health care to people living with HIV/AIDS.

Public Health Providers and Government

Interventions, counseling and testing campaigns, and educational programs are among the means that have been attempted and need to continue in order to stop the spread of this disease.

Interventions have targeted all pregnant women who are HIV infected, all infants born to mothers who are HIV positive, all persons with CD4 (a glycoprotein found on the surface of immune cells) of less than or equal to 350 CD4 Cells/mm3, and all persons with TB who are co-infected with HIV/AIDS. The measures have resulted in substantial increases in public sector expenditure.

A national HIV/AIDS counseling and testing campaign reached about 13 million people against the target of 15 million by June 2015 (the 15 by 15 campaign). This campaign was implemented throughout South Africa with the collaboration of government, non-governmental, and business sectors. Counselling and testing were done at health facilities, non-health facilities, and at nationally and provincially organized mass events. The essential lessons from the “15 by 15” campaign are immediately valuable for global efforts to end the AIDS epidemic as a public health threat by 2030. As a central component of the effort to end the epidemic, the world has embraced a new target for antiretroviral therapy. Ambitious new targets for primary HIV prevention and non-discrimination would reduce the number of new HIV infections by 89% by 2023 and the number of AIDS-related deaths by 81% (UNAIDS 2015, 19 July; updated 2019 October 01). Success in reaching the “15 by 15” goal shows that it is possible to end the AIDS epidemic (New UNAIDS report. Accessed February 2020.

HIV/AIDS, being a human catastrophe, requires urgent health education on human sexuality, with particular emphasis on training family leaders, clergy and laity, and civil society actors. Appropriate information and teachings in several public health areas are needed, which can allow them to properly play their role in the fight against HIV/AIDS.

Educational programs to prevent HIV/AIDS should be user-friendly and age-appropriate. Particularly, these programs need to be attractive to the maturity level of the elderly who are, in most African countries, considered as pillars of morality. Programs should feature cultural aspects that promote health which the elderly have used throughout their lives in order to increase acceptability of HIV/AIDS prevention by the elderly. They will, in turn, be motivated to help the younger generations take steps to prevent acquiring and passing on HIV/AIDS.

Church

The fight against the spread of this scourge through the church can contribute positively in reducing the spread of the pandemic and convince people to walk in God’s will for a better life. The pandemic provides the opportunity for the church to fight against HIV/AIDS and to strengthen its holistic mission.

People living with HIV/AIDS are generally in a dire need of spiritual, moral, psychological, social, material and financial support. Therefore, the Church in sub-Saharan Africa can raise and make available the necessary support. De la Porte (2006, i) and Adogame (2007, 481) insist that Christian education and ethical values development are important factors. Through these, the church can help develop ethical individuals and communities who can both stop HIV/AIDS and carefully support persons living with the pandemic.

The enormous consequences of HIV/AIDS and the persistent pressure to educate African families, church leaders, and community members has started to bear fruit. Reporting on HIV/AIDS support work by African Pentecostals, Adogame has demonstrated that the project empowers individuals and families to prevent HIV/AIDS by using peer education, interpersonal communication and counselling, spiritual counselling, drama, and HIV/AIDS education modules in the church’s Bible college curriculum. For individuals, the church offers peer education and counseling to promote risk reduction behaviours. For families, the church emphasizes parent-child communication and conducts seminars to empower parents to discuss sexuality issues frankly in the context of their faith and the growing epidemic (Adogame 2007, 478).

However, many ecclesiastical communities and churches in sub-Sahara Africa still remain uncommitted to the fight against HIV/AIDS . Worried by such church attitudes and behaviours, Ludollf advises: “Churches have not been very involved in the struggle against AIDS, while the church should have the solutions to the world’s problems. Now is the time to make a real difference” (Ludollf 2006, 110).

Conclusion

HIV/AIDS is an added burden to the challenges that Africans face and have traditionally faced. Therefore, it is relevant to mobilize all African forces to promote positive transformation and stimulate a mental and behavioural change. It is therefore important to encourage and motivate families, churches, and all public health institutions that can adequately contribute to promote sex education, without complacency or shame, in accordance with God’s Word. Church leaders can include public health education for the elderly and focus specifically on HIV/AIDS prevention with the young people. The Church should promote community support groups for all people affected.

Religious and traditional services should form the basis of emotional and psychological support for all affected and infected people. A multi-sector collaboration and community mobilization, including people living with HIV/AIDS, are vital for sustainable solutions (Lekalakala-Mokgele 2011, 4). It is essential that the Church facilitate and revitalize Christian families in the fight against HIV/AIDS.

The task of the community of public health providers, church, and family, is to encourage each member to get tested and to know their status in relation to HIV/AIDS. Public health trained agents must provide spiritual, moral, material, and psychological encouragement to every person living with HIV/AIDS. These people need support that is medically compliant that includes taking care of the individual and promoting neighborly love in the community. The church can act as a catalyst regarding conflict and misunderstandings and contribute toward sexual ethics and education to help African people.

References

Adogame, A 2007. HIV/AIDS Support and African Pentecostalism: The Case of the Redeemed Christ Church of God (RCCG). Journal of Health Psychology. http://hpq.sagepub.com/content/12/3/475.refs.html.

Dill, J. and A. De la Porte. 2006. Choose Life: A Value-based Response to HIV and AIDS. Pretoria: CB Powell Bible Centre, UNISA.

Kalemba, M. 2017. Le VIH/AIDS, Les conceptions africaines de la famille, de la sexualité, du VIH/AIDS et l’évolution de ce fléau. Paris: Excelsis.

Lekalakala-Mokgele, E 2011. A Literature Review of the Impact of HIV and AIDS on the Role of the Elderly in the Sub-Saharan African Community. Health SA Gesondheid 16, no. 1: 1-6.

Ludollf, A 2006. Training youth leaders for an HIV and AIDS youth programme, Choose Life: A Value-based Response to HIV and AIDS. Pretoria: CB Powell Bible Centre, UNISA.

Makiwane, M. et al. 2004. Experiences and Needs of Older Persons in Mpumalanga. Pretoria: Human Sciences Research Council.

Mampolo, M. 1985. Amour, sexualité et marriage. Kinshasa: CEPROPASKI.

Pongo, M. 2018. Théologie et le VIH/AIDS. Kinshasa: Med.

Ramos, R. et al 2000. International Conference on AIDS, USA July 13-14. New York.

Robert, P. 1964. Dictionnaire alphabétique et analogique de la langue française, Société du Nouveau Littré, Paris.

Santedi, L 2004. La mission prophétique de l’église famille de Dieu en Afrique. Perspectives post-synodales, dans une théologie prophétique pour l’Afrique. Kinshasa: Mediaspaul.

Schatz, E & C. Ogunmefun. 2007. Caring and Contributing: The Role of the Older Women in Rural South African Multigenerational Households in the HIV/AIDS Era. World Development 35, no. 8: 1390-403.

Sproul, R.C. 1995. New Geneva Study Bible. Nashville: Thomas Nelson Publishers.

UNAIDS. 2011. Global HIV/AIDS Response: Epidemic Update and Health Sector Progress Towards Universal Access. UNAIDS. http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/progress_re.

______. 2012. Global AIDS Response Progress Report 2012. http://www.unAIDS .org.

_______. 2013. World AIDS Day Report. 2012: Results. UNAIDS. http://www.unAIDS .org.

UNAIDS and UNICEF. 2004. Children on the Brink. 2004: A Joint Report of New Orphan Estimates and Framework for Action. New York: UNAIDS.